Sustainable-investing (SI) fund labels have gained significant prominence in recent years as tools to provide transparency and drive capital towards the green transition.

A recent Qontigo whitepaper1 examined the criteria used in the 12 most important frameworks setting standards for SI products in Europe, to highlight the discrepancies among the various labels and inform interested stakeholders about the intricacies of the current situation. The study provides a like-for-like comparison of exclusionary criteria and portfolio-construction techniques as applied in each individual label.

On February 24, Qontigo and Responsible Investor hosted a webinar to discuss the state of play in Europe’s ESG labeling landscape. A panel of experts discussed the aims of the labels, their intersection with broader European regulation, and what it all means for the ultimate goal of achieving a more sustainable economy.

Anna Georgieva, Qontigo’s Associate Principal for Sustainable Investment and co-author of the recent whitepaper, moderated the panel. Fund design has great implications for the growth of sustainable investing, she said, and asked the speakers whether the current assortment of labels may hinder the development of investment products.

“In the current landscape, frameworks proliferate and cover a wide range of objectives,” said Georgieva. “Even a simple look at the labels’ names — SRI, ESG, sustainability, green, climate — reveals this diversity. Ironically, alignment with European Union (EU) rules is itself a source of divergence. The interpretation of sustainability or investor preferences is not yet uniform across EU legislation.”

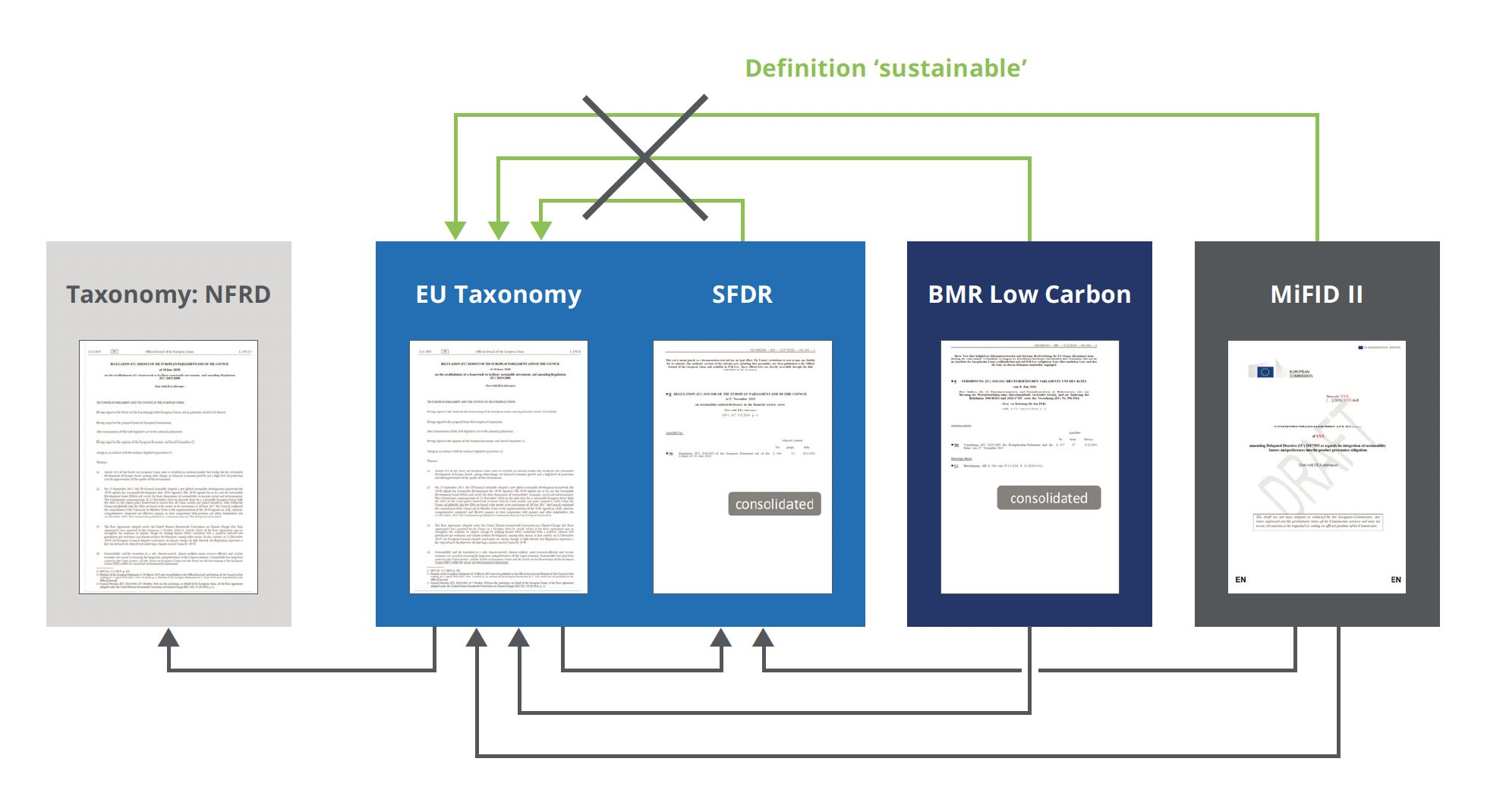

Markus Zellmann, Legal Counsel at Deutsche Boerse Group, first tackled the overarching problem of misalignment within EU sustainability legislation. The EU Taxonomy, he said, was conceived as a Europe-wide classification of environmentally sustainable economic activities. However, a delay in the introduction of the Taxonomy vis-a-vis other initiatives that were meant to fall under its scope, such as the EU’s Low Carbon Benchmarks Regulation (BMR) and the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), has left investors facing overlapping yet divergent rules, and differing definitions of what sustainable is.

“This makes it very complex to handle,” Zellmann said. “By way of an example, if you are a benchmark administrator and you create a sustainable benchmark under BMR, like a CTB/PAB2 index, it is not said that those fit the definitions of what’s sustainable under the SFDR or the Taxonomy.”

“Currently we have a high number of labels defining what is sustainable, and have some regulation, but the coherence of those regulatory standards is low,” Zellmann said. He added that the introduction and expansion of the EU Taxonomy could change this.

Figure 1 – Major EU sustainability regulations

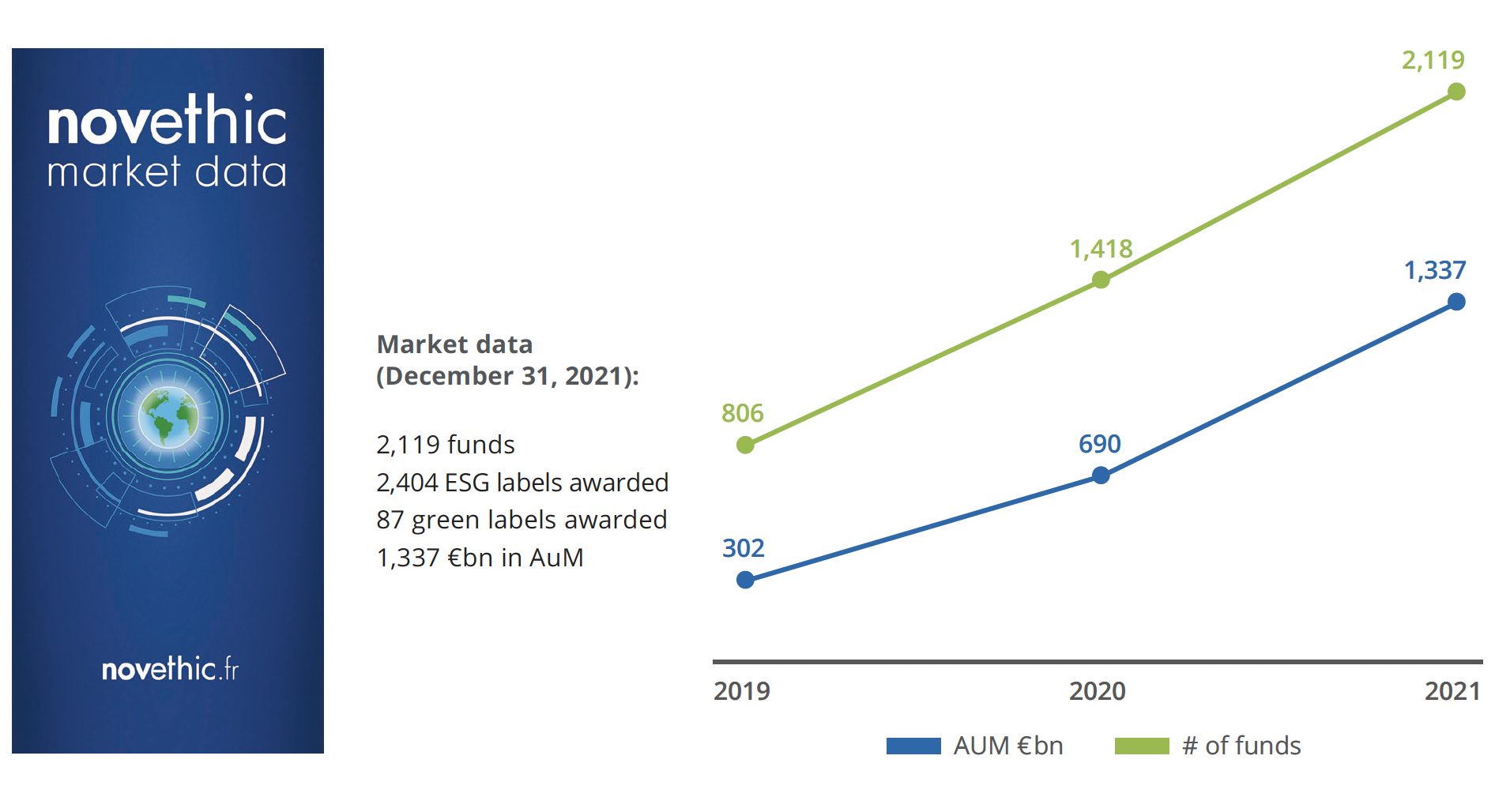

The influence of green labels in Europe is not to be underestimated. Novethic, which researches and audits sustainable investments, has counted more than 2,100 funds, with a total of EUR 1.3 trillion, that have been awarded European labels (Figure 2). Over 300 funds have at least two labels, and some have up to four, an indication of the differing goals and scope of the various frameworks.

“No one size fits all,” said Nicolas Redon, Green Finance Expert at Novethic. “There are different types of labels. If you are both investing in green, but conducting ambitious engagement as well, your green label will not necessarily reward the fact that you’re conducting engagement. If you do a lot in your strategy and want to see that rewarded, you can take different labels. And then there are also national regulatory requirements in place.” For example, Redon explained, French law requires at least one labeled fund “in the offer of each multi-fund life insurance policy in the country — so there is a need for asset managers to get those labels in order to be distributed by unit-linked products in these life insurance policies.”

Figure 2 – European labeled funds

Tom Van den Berghe, Managing Director at Belgium’s CLA, which governs the country’s Towards Sustainability (TS) label, gave the perspective of a labeling agency. He explained that TS seeks to evolve alongside emerging regulation, client preferences and scientific research, as well as establish equivalences with other labels in Europe. Three-year-old TS has been intentionally positioned as a broad ESG label, he said.

TS “is not the strictest dark green label, but that was never the intention,” said Van den Berghe, who is also Director for Sustainable Finance at Febelfin, Belgium’s financial sector federation. “The challenges we have are so broad that we need the involvement of all players to reach sufficient impact. We cannot limit ourselves to niche initiatives. We don’t want to have a label that is only suitable to the more convinced green investors — we also want to have a sustainable offer for more conservative investor profiles.”

“We’ve chosen to create a set of minimum standards for an SRI (Socially Responsible Investing) product, the minimum level of sustainability a product needs to obtain to be credible as being sustainable,” he said. “It is a minimum standard but nonetheless it is quite ambitious. It is a pre-requisite, and then you can go beyond the label and formulate your own criteria or expectations on sustainability.”

Challenges

Van den Berghe also said that a functional label should strike a balance between sustainability approaches, for example exclusions vs. engagement, and find an equilibrium between financial returns and sustainability objectives. Novethic’s Redon, whose firm audits France’s Greenfin label, added that it is currently very difficult for issuers and investors to accommodate the many exclusions found across different labels, with the fossil-fuel sector being a prime example of this challenge.

Another topic that was touched upon during the debate was the multiplication of SFDR Article 8 and Article 9 stamps, which are disclosure standards rather than labels.

“In the vast area of products which are Article 8-compliant, you need more explanation of how your product is sustainable,” said Zellmann of Deutsche Boerse. “That’s not really anything that is comparable or tangible for an investor. Just because the product is Article 8, it means nothing; you need a label or other measures like a taxonomy-based assessment, to understand whether it is green or sustainable at all.”

What effect the EU Taxonomy will have on this landscape remains to be seen, according to Zellmann. The European classification could make some labels obsolete, as the reporting of Taxonomy-aligned revenues in a transparent way would enable investors to choose what best fits their profile. At the same time, some labels could remain relevant to cater to specific investor needs.

“In the future, the legislative approach will be more coherent and will focus more on the Taxonomy,” Zellmann added. “The Taxonomy’s scope will be wider, and that will have an impact on requirements for labels.”

Impact investing

To finish, the panel was asked if impact investing is well served by current labels.

Van den Berghe said labels are frequently used as engagement tools, but also act as a more direct lever for corporate change: he mentioned that the Belgian labeling agency has received calls from companies seeking information to align processes with the label’s guidelines.

Conclusion

As the discussion showed, country labels have become deeply embedded in the distribution of investment funds within the many national markets. Qontigo’s Sustainable Investment Team has argued that labels have the potential to influence the success of the sustainability transition, but currently form a highly divergent and fragmented field. Investors, intermediaries and fund issuers navigating this landscape will only see their due-diligence tasks increase as new EU rules frameworks become established.

Overall, the webinar provided an enlightening exchange of ideas around a topic that will only gain precedence in coming months.

1 Georgieva, A., Mehrotra, S., ‘Sustainable investment fund labeling frameworks: An apples-to-apples comparison,’ February 2022.

2 The European Union Climate-transition Benchmarks (CTBs) and Paris-Aligned Benchmarks (PABs) follow EU rules establishing Climate Benchmarks standards that came into application in 2020.