By Anna Georgieva, Senior Sustainable Investment Specialist at Qontigo

Awareness of our interconnectedness with other species grew rapidly in 2020 as it became clear that unsustainable development increases the risk of disease pandemics such as COVID-19.1 In 2021, efforts to halt nature loss are set to accelerate further — with a key role to be played by investors.

This year’s UN Biodiversity Conference in May in Kunming, China, is expected to set global goals to bend the curve on biodiversity2 loss by 2030 and achieve complete biodiversity recovery by 2050, an event that may be a potential watershed akin to what the 2015 Paris Agreement did for climate.3 In its lead-up, a group of more than 50 countries aiming to secure a global agreement to protect at least 30% of the planet’s land and ocean by 2030 launched last month at the One Planet Summit.4 Meanwhile, regulators are stepping up pressure on companies to disclose their impact on nature.

With sustainable investing gathering pace, money managers globally are introducing new environmental funds and uncovering novel biodiversity measurement tools that open up new possibilities in the field. Besides heightened awareness of the risk and regulatory implications, investors have one more reason to take note: protecting habitats is essential to combat climate change and meet global sustainability goals — objectives already well-embedded in national legislation and investors’ policies.

A threat to life and economic value

The degradation of natural capital impairs the valuable ecosystem services that people and businesses depend on for health and prosperity. The World Economic Forum has estimated that more than half of the world’s gross domestic product — USD 44 trillion — is moderately or highly dependent on these ecosystem services.5 For investors and governments, biodiversity loss has significant economic consequences that should be recognized in national accounting systems and corporate bookkeeping.

Companies face a direct threat from biodiversity loss as a result of physical, transition, regulatory and systemic risks. A UK Treasury report6 early this month outlined the stark financial cost of rapid biodiversity loss, and recommended that governments integrate natural capital into national accounting systems7 and that businesses and financial institutions measure and disclose their dependencies and impacts on nature. In another landmark study8 last June, the Dutch Central Bank concluded that financial institutions in the country have EUR 510 billion in exposure to biodiversity risks such as disruption of animal pollination.

Rapid degradation in life stock

These risks have escalated amid an alarming rate of biodiversity deterioration. The population sizes of living species have decreased 68% on average since 1970. The fall-off is as high as 94% in the case of Latin America.9

Changes in land and sea use caused by unsustainable agriculture, logging, transportation, development, energy production and mining are the key drivers of this loss. More than half of the world’s habitable land area and 70% of freshwater is already used for agriculture, which is also the single-biggest greenhouse gas emitter. The effects of climate change, species overexploitation, pollution and invasive species all deplete Earth’s natural diversity too.

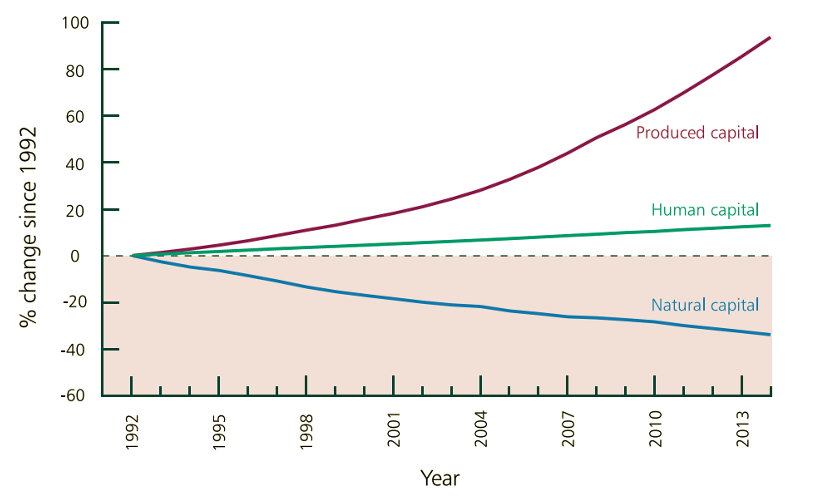

By another estimate, the value of the stock of natural capital has declined by nearly 40% since 1992, while global production has surged, and human capital only increased about 13% (Exhibit 1).10

Exhibit 1 – Relationship between production, human wealth and biodiversity loss

Turning this natural collapse around is estimated to need an additional USD 711 billion on average per year beyond current measures.11 This is where investors and asset managers can step in, steering capital away from companies with nature-related risk and towards regeneration projects.

Link to climate change

While attention is crystallizing on biodiversity, the topic has long been present in sustainable strategies through efforts to combat climate change and promote societal goals. For example, deforestation is among the biggest causes of rising greenhouse gas emissions. More than 80% of the assessed targets for the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are reliant on biodiversity and ecosystems for their delivery.12

Governments and financial institutions already invest trillions of dollars in infrastructure, climate mitigation and development assistance. With smart adjustments there is growing appetite to direct these away from technological solutions and towards ‘nature-based solutions’ – i.e. using the world’s forests, grasslands and wetlands as a means to combat climate change using nature’s capacity to absorb and store greenhouse gases. Indeed, scientists believe such nature-based solutions can achieve a third of the cost-effective carbon reduction needed annually by 2030 to meet the 2℃ target.13

Major companies are already starting to deploy these solutions. For example, Olam, a leading agri-business that sources from around 5 million farmers globally, is planning a blockchain-powered carbon trading platform based on sustainable land use management practices. Nestlé is now planting trees within its supply chain, which benefits local suppliers, contributes to climate-resilient farms and aligns the Swiss company with its net-zero targets.14

Awareness is now leading to concrete action in the investment industry too. Last September, two dozen financial institutions signed the Finance for Biodiversity Pledge and committed to protect and restore ecosystem services through their finance activities and investments.15 The recently-launched Natural Capital Investment Alliance promotes nature as an investment opportunity and aims to mobilize USD 10 billion towards this goal by 2022.16

On the asset-management side, Pictet, Mirova and AXA are among firms that have very recently launched funds targeting an environmental impact strategy. More are known to be on the works, as managers develop innovative methods to link data about the natural world with companies’ operations.

The Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) last September presented a strategy paper where it urges its more than 3,000 signatories (which together oversee more than USD 100 trillion) to take urgent action to halt biodiversity loss.17 Given the increasing weight of PRI guidelines and expectations in the investment community, this latest report may act as yet another catalyst to channel money flows towards the protection of natural capital.

The data challenge

Data remains a major challenge. Unlike greenhouse gas emissions, deciding on a global, universally-agreed metric for biodiversity loss is not easy. Specific, localized quantitative indicators that don’t sacrifice quality for greater coverage are needed. Biodiversity risk metrics must be clear if they are to be used in portfolio analysis. In essence, data must be fit for purpose and track drivers of biodiversity loss that can be changed to help replenish diversity.

Several collaborative initiatives aim to evaluate corporate exposure to biodiversity impact, employing different tools and methods. For example, in January 2020, four major French investors launched a call to action to create a provider of sound biodiversity-related metrics and indicators of the effects of investments on natural capital. Other firms joined their quest, pulling a combined EUR 64 trillion in assets under management behind the campaign.18 Meanwhile, several Dutch financial institutions have formed a Partnership for Biodiversity Accounting Financials to develop a common measure for the positive biodiversity impacts of their investments.19

Existing measurement approaches include the Global Biodiversity Score, the Biodiversity Footprint for Financial Institutions, the Corporate Biodiversity Footprint and Biodiversity International’s Agrobiodiversity Index. There are also incipient steps to align the various approaches.

Many investors are following individual efforts, incorporating environmental data sets into their portfolios and investment decisions. They have either developed bespoke scoring methods or have employed third-party information.

One such data set is satellite imaging — already used to measure physical climate risk. Dutch asset manager ACTIAM has partnered with Satelligence, a geodata analytics firm, to monitor investee companies’ deforestation impacts through images and artificial intelligence.20

The plethora of innovative approaches to information gathering is promising, and shows that while challenging, the data issue will eventually be surmounted.

Regulation pressure will build up

Regulators are also putting the focus on companies’ biodiversity footprint and may soon demand more disclosure.21 France is one step ahead: the government is extending its pioneering Article 173 legislation to demand asset owners and asset managers report their biodiversity impact as of this year.

Europe is taking a strong lead in seeking environmental data. The European Commission is currently reviewing a Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) and preparing a renewed sustainable finance strategy, both of which are likely to lead to increased biodiversity reporting requirements on companies. The highly-anticipated EU Taxonomy, which will determine what business activities are sustainable, integrates biodiversity by monitoring whether companies contribute towards — or hamper — six environmental objectives.22

The official launch of the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD)23 this year may add further impetus to data disclosure by helping companies better assess and report their environmental track record, a crucial tool to shift finance toward nature-based solutions. The TNFD follows on the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), which has successfully helped integrate climate change-related information into mainstream financial reporting.

Indexing can help, as it did with climate investments

Passive investing will also play a role, just as it has done in recent years with low-carbon and ESG solutions that help investors adopt responsible strategies in a simple and efficient manner. Assets in ESG ETFs more than tripled in 2020 to USD 189.8 billion.24

At Qontigo, increasing innovation and data availability has allowed us to design indices that accurately gauge companies’ climate and societal impact. For example, our Climate Benchmark Indices incorporate Scope 3 carbon emissions and science-based targets. The STOXX® Global ESG Leaders Index selects companies based on deeply researched corporate data provided by Sustainalytics. Biodiversity is high on our radar, and we envisage similar possibilities in the field.

Work ahead

The fight against biodiversity loss is intensifying, driven from multiple angles. Just as with climate action, the role of investors will be pivotal. And despite recent evidence of progress, much remains to be done: in a ShareAction poll of the world’s largest asset managers published last June, not one of the 75 respondents had a dedicated policy on specific biodiversity risks and impact.25

The world needs a framework and a set of commonly agreed targets that can guide governments and regulators in setting policy and rules — targets around which states, companies, investors and the public can coalesce. In this sense, 2021 may well prove to be a breakthrough year for biodiversity action.

To enquire about Qontigo’s ESG and Sustainability solutions, please e-mail us at marketing@qontigo.com.

1 See Jeff Tollefson, ‘Why deforestation and extinctions make pandemics more likely,’ Nature, Aug. 7, 2020.

2 Biodiversity is the rich variety of life on earth, occurring at the species, ecosystem and genetic levels. Loss of biodiversity undermines life itself, but it also has immediate and acute effects on wellbeing, development, economic growth, global security and equity.

3 See Convention on Biological diversity, ‘Zero Draft of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework.’

4 High Ambition Coalition, press release, Jan. 8, 2021.

5 ‘Nature Risk Rising: Why the Crisis Engulfing Nature Matters for Business and the Economy,’ World Economic Forum, January 2020.

6 Dasgupta, P., ‘The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review,’ HM Treasury, 2021.

7 See work already undertaken by the Inclusive Wealth Index, Inclusive Wealth Report 2018. Environmental profit and loss accounting (EP&L) has also been deployed by the private sector by companies such as Kering.

8 ‘Indebted to nature – Exploring biodiversity risks for the Dutch financial sector,’ De Nederlandsche Bank, Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving, Jun. 19, 2020.

9 ‘Living Planet Report 2020,’ World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

10 Managi and Kumar, eds., Environment Programme’s ‘Inclusive Wealth Report’ 2018 as it appears in Dasgupta (2021).

11 Source: The Paulson Institute, The Nature Conservancy and Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability, ‘Financing Nature: Closing the global biodiversity financing gap,’ 2020.

12 Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, IPBES, 2019.

13 ‘Natural climate solutions,’ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, October 2017.

14 Tropical Forest Alliance, ‘What nature can do for the climate in a post-COVID world,’ Nov. 9, 2020.

15 See Finance for Biodiversity Pledge.

16 Susanna Rust, ‘New natural capital investment alliance aims to mobilise $10bn,’ IPE, Jan. 11, 2021.

17 ‘Investor action on biodiversity: discussion paper,’ PRI, Sep. 1, 2020.

18 See ‘AXA IM, BNP Paribas AM, Mirova and Sycomore AM launch joint initiative to develop pioneering tool for measuring investment impact on biodiversity,’ Jan. 28, 2020.

19 See Partnership for Biodiversity Accounting Financials.

20 ‘ACTIAM employs satellite data to combat deforestation,’ ACTIAM press release, Sep. 16, 2019.

21 ‘NGFS to turn its gaze to biodiversity loss,’ Environmental Finance, Dec. 22, 2020.

22 The Taxonomy Regulation establishes six environmental objectives: climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation, sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources, transition to a circular economy, pollution prevention and control, and protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems.

23 The TNFD is being catalyzed through a partnership between Global Canopy, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

24 TrackInsight data.

25 ‘Point of No Returns, Part IV – Biodiversity,’ ShareAction, June 2020.